【Professor Sanjay PAREEK, Dr. Eng.】“How do you like FUKUSHIMA?”

Style Koriyama special interview in English.

“How do you like FUKUSHIMA?”

We’re asking people from around the world about their experiences in Fukushima in this relay-style interview series.

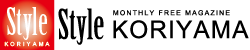

This time, we spoke with Dr. Sanjay Pareek, a Professor of Engineering at Nihon University, who teaches building materials and structures at the College of Engineering.

He shared what brought him to Japan, his impressions of Japanese life and culture, his studies, and more.

Professor Sanjay PAREEK, Dr. Eng.

Where are you from?

I’m from Jodhpur, India. Jodhpur is a historic city, home to the stunning Mehrangarh Fort and several magnificent palaces, including the Umaid Bhawan Palace. The Maharaja of Jodhpur is also very well known locally. My city has fought many wars for its independence and was never defeated, so we take great pride in our heritage.

.jpg)

Meharangarh fort

Umaid Bhawan Palace

↓With Maharaja of Jodhpur at Umaid Bhawan Palace.

In India, we celebrate many festivals, especially for Hindus. Diwali, the festival of lights, is one of the biggest and falls in October or November. Holi, the festival of colors, is celebrated in March or April.

Our calendar is based on a unique combination of lunar and solar calculations. The new year begins in Chaitra, just after the Holi festival, around March or April.

↓At Holi festival in Jodhpur.

What did you do for fun as a child?

↑With his mother when he was 4 years old.

In my childhood, I used to play cricket and badminton. After finishing primary school, I went to Nigeria, where I played soccer—the most popular sport there.

Because my father worked for the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, I moved around a lot as a child. I lived in several places, including Jodhpur and Mumbai in India, Ibadan in Nigeria, and Tripoli in Libya. After graduating from high school in Nigeria, I returned to India for my bachelor’s degree. Later, I completed my graduate studies at Nihon University in Koriyama.

↓With his young brother and young sister.

↓He studied in Nigeria when he was 12 years old.

What brought you to Japan?

When I was in India, I learned about Professor Yoshihiko Ohama, who was conducting in-depth, original research in the field of polymer concrete. My father met Professor Ohama at an international conference in Libya and told me about his work. I was very impressed by his extensive research and found it fascinating.

I read many of his research papers and became inspired to pursue similar research, aiming to earn my master’s and doctorate in the field. At that time, there was no internet or email, so I corresponded with him by letters. Professor Ohama was also interested in having me join his research team and invited me to Japan for my higher studies.

↓He saw snow for the first time in Japan. With Professor Ohama.

When you came to Japan the first time, did you feel some differences between India and Japan?

Yes, the biggest challenges were mainly with language, food, and culture. Since we use English and Hindi in India, I had no background in Japanese. When I first arrived in Japan, the language was a huge barrier for communication and handling official work. I could hardly talk to any of the students in my lab because they didn’t speak English. Most of the time, I couldn’t communicate with anyone, even though there were always many students in the lab. It was very frustrating.

I studied Japanese hard to overcome this barrier. Now, I teach building materials science to Japanese university students entirely in Japanese, and I also review and correct their theses. I can do this because I am now fluent in the technical language.

I’m a Hindu by religion and a Brahmin by caste, so I was a vegetarian. In our community, Brahmins don’t eat meat, fish, or eggs.

When I came to Japan, it was very difficult to find vegetarian options in restaurants or cafeterias. Usually, there was only salad, or maybe bread—but most bread contained eggs, so even that wasn’t always suitable.

Did you make the food by yourself?

No, I was very busy with my studies at the university, so every day I ate only bread, salad, and milk. As a result, I lost weight and had very little energy. I called my mother to explain my stressful situation. She told me that God had sent me to a country where I needed to survive, so I had to eat whatever people eat there.

I prayed for forgiveness and decided to be more flexible with food. Now, I enjoy most Japanese dishes and no longer keep strict dietary restrictions. Incidentally, my wife is Japanese, and she makes excellent Indian and Japanese food. Over time, I’ve developed a real taste for Japanese cuisine and enjoy it very much.

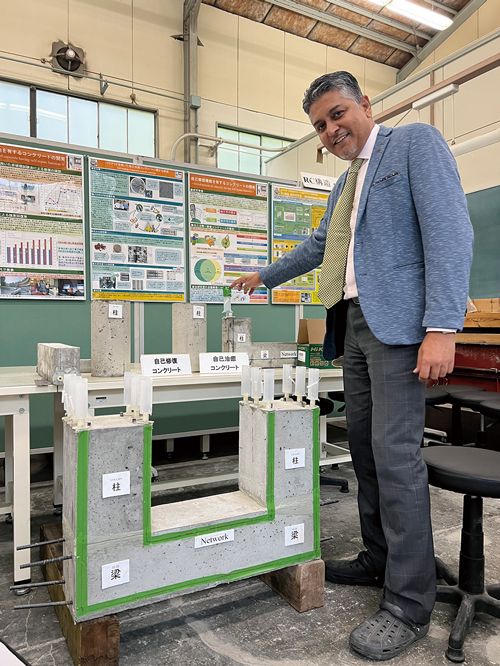

↓Wedding at the Umaid Bhawan Palace in India.

The culture wasn’t too difficult to understand because Japanese and Indian cultures are quite similar. In both countries, we adjust the way we speak depending on whether someone is older, younger, or the same age. In India, we use honorific expressions to show respect to older people, and younger people learn from and follow the guidance of those who are older—just like in Japan.

↓He got a doctorate at Nihon University. He went on the stage at Budoukan as a student representative.

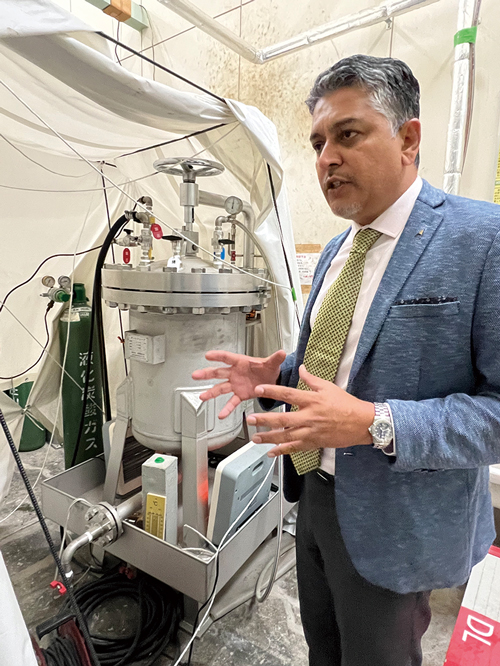

What have you been researching recently?

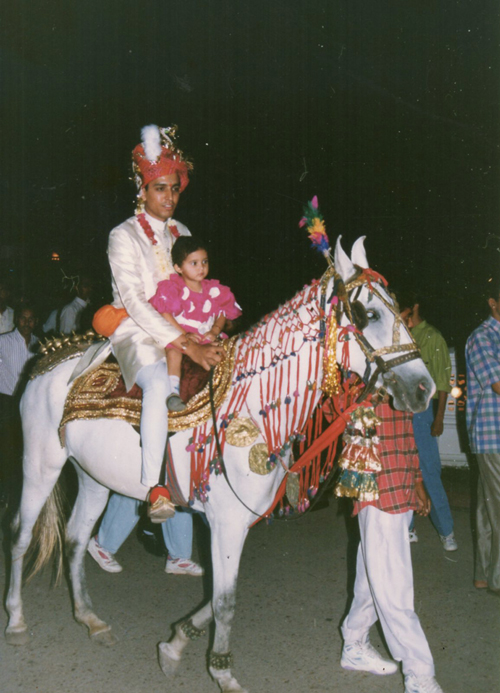

My research mainly focuses on self-healing (self-repairing) concrete. I’m also working on developing concrete that doesn’t use cement.

The third area of my research is the development of a concrete battery, for which I am currently applying for patents.

Almost all batteries are alkaline, and concrete is also naturally alkaline. By adding a special material, we can generate enough power to light a lamp. Even during a major earthquake, this concrete can provide light. All of my research projects focus on the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), so my lab’s main motto is SDG-oriented materials.

I also want to contribute to India, so I’m developing non-fired (non-baked) bricks. Normally, bricks are made from clay and baked with coal to make them strong, which consumes a lot of energy. My approach uses fly ash, a byproduct from coal-fired power stations, to make bricks without baking. In India, most electricity comes from coal, which produces both carbon dioxide and large amounts of fly ash waste. Non-fired fly ash bricks can help reduce waste, save energy, and cut carbon dioxide emissions.

What is your favorite place in Fukushima?

My favorite natural spot is the Inawashiro lakeside on Mount Bandai, and my favorite man-made site is Ouchi-juku. I love Ouchi-juku because it brings to life the old travelers’ rest houses from the Edo period, used by people journeying to northern Japan. It’s a well-preserved historic site. If you want true peace of mind, you can enjoy the mountains and Lake Inawashiro there.

In addition, the historical city of Aizu-Wakamatsu, with its rich samurai culture and the legacy of the Byakkotai, is also very impressive.

What would you like to do in the future?

I want to bring more Indian students to Japan and send Japanese students to India to promote cross-cultural exchange in education and technology. India is developing rapidly and needs technology transfer from Japan, while Japan also needs many young engineers to support its local industries. Through these exchanges, I hope to strengthen the friendship between our two countries.

How do you feel about Fukushima after experiencing the Tohoku earthquake?

The earthquake was a massive disaster for the communities in the Tohoku region. The explosion at the nuclear power plant worsened the tragedy, causing long-term social and environmental impacts due to nuclear contamination in Fukushima.

While it took only about 6–12 months to repair basic infrastructure damaged by the earthquake, the problems caused by the nuclear reactor were much more severe and are still ongoing. I feel deeply saddened by this and hope that such a tragedy never happens again.

Have you helped nuclear power station problems with your research?

Yes, I began research on developing concrete that blocks radiation. This is a high-density concrete, and containers made from it have been used to store radioactive waste. I firmly believe that as a researcher, you should use your work to help the local community.

I focused on finding an optimal solution for storing radioactive waste and succeeded in developing high-density concrete to support our local society. I strongly believe that researchers and educators should think about how to help their own communities, because we are part of society. Many people focus on publishing papers or working abroad, but I think it’s more important to address local issues first before thinking globally.

The idea of developing a concrete battery came from my desire to address urgent local problems. During floods or earthquakes, power outages are common, so I wanted to create something like a concrete battery to help communities in these situations. I am always thinking about how to use my research to support society during natural disasters and conserve electricity.

Finally, could you give Style Koriyama readers your message?

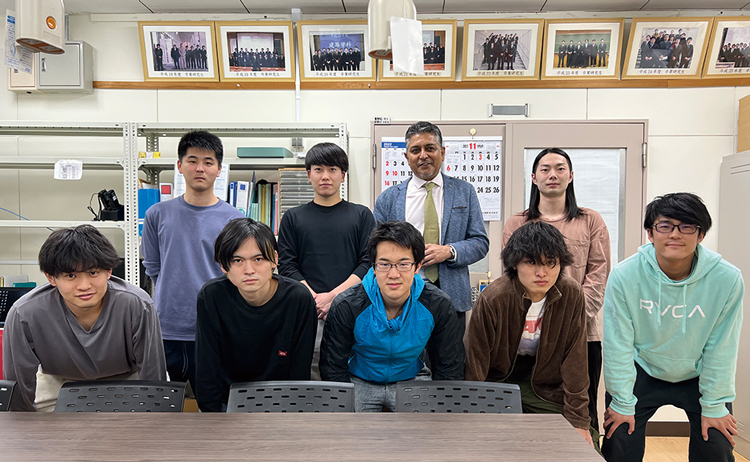

As a researcher and educator, I want to support students from various schools in Fukushima. Many of my students are from abroad, and coming from a foreign background myself, I try to provide them with the knowledge and perspective needed to understand global conditions. I encourage my students to study abroad and experience other countries both culturally and professionally, so they can apply their skills in Japan or elsewhere.

Being from India and having traveled to many countries, I aim to inspire young people to work in international environments. Japan is a small country, and its business, education, and technology sectors are already quite developed. To make a global impact, we need to focus on supporting growth in Asian, African, and South American countries.

↓With the laboratory members at Nihon University.

<Profile>

Professor Sanjay PAREEK, Dr. Eng.

• Graduated Abadina College, Ibadan, Nigeria in 1983

• Graduated University of Rajasthan, Jaipur, India in 1986

• Entered Department of Architecture, Nihon University Faculty of Engineering as research student in 1987

• Started master’s course in architecture at Nihon University Faculty of Engineering in 1988

• Obtained doctorate in architecture at Nihon University Faculty of Engineering, and joined Daito Concrete in 1993

• Left Daito Concrete in 1996, and became an Assistant professor in the Department of Architecture, Nihon University Faculty of Engineering in 1996

• Became a full-time Lecturer in the Department of Architecture, Nihon University Faculty of Engineering in 2000

• Promoted to full-time Associate professor in the Department of Architecture, Nihon University Faculty of Engineering in 2008

• Promoted to full-time Professor in the Department of Architecture, Nihon University Faculty of Engineering in 2018